I am watching and reading with fascination all the materials, that give me insight into the Russian Psyche. Reportages from Russian independent online TV Current Time about ordinary Russians who, when the doors from their outhouse fall apart, don’t just get a screwdriver and fix the broken hinge, but write letters to Putin instead. I am watching the fascinating Youtube series by the Polish traveller Michał Pater, who, after many years, retraced his steps from a hitchhiking trip to the Russian far east to see with his own eyes, how much the atmosphere and mentality in Russia changed after their nation unleashed full scale war on Ukraine. Those vox pops published by the 1420 channel in which ordinary Russians answer sometimes meager, and sometimes provocative questions are also fascinating. Recently Deutsche Welle published a few reportages about how Baltic States deal with Russian significant Russian minority living in their territory as well. And this is yet another fascinating insight into the soul of post-soviet Russian.

Quick background: during Soviet Times, millions of ethnic Russians moved – or were moved – to the occupied territories. Those, along with truly Soviet Citizens (like an acquaintance of mine, whose parents come from two central-Asian former soviet republics, and she herself grew up in Hungary, where her father, a Red Army officer was based, before moving to Estonia just before the collapse of the Soviet Union) often weren’t thinking of themselves as occupants. They just lived in the realities of the Soviet Union, moving around for work or family reason, without thinking about the fact that Baltic States used to be independent countries. For many of them it was no different to a Polish man today, who moves from Kraków to Szczecin – nobody in Poland today thinks twice about the fact, that Szczecin used to be a German city of Stettin before the WW2. The difference is, that after the Baltic states regained their independence, those people suddenly found themselves leaving on the territory of the nation state, that was not particularly keen of being part of Russian or Soviet empire in that or another form.

For the governments of those newly re-established republics, hundreds of thousands of Russians (and Soviet citizens) was a potential issue. They had to consider security repercussions. If we remember, that Russia uses alleged discrimination of Russian speakers in Donbas as an excuse for their invasion of Ukraine – rightly so. They could not just hand out Latvian or Estonian passport (Russian minority in Lithuania is much less significant) to hundreds of thousands of people who at best did not feel any connections to the states they found themselves living it, at worse felt like a victims of history, hurt that their privilege (that Russians enjoyed within the Soviet Union compared to the occupied nations) was suddenly taken away from there. If 1/4 of people in your country is like that, this really becomes a problem.

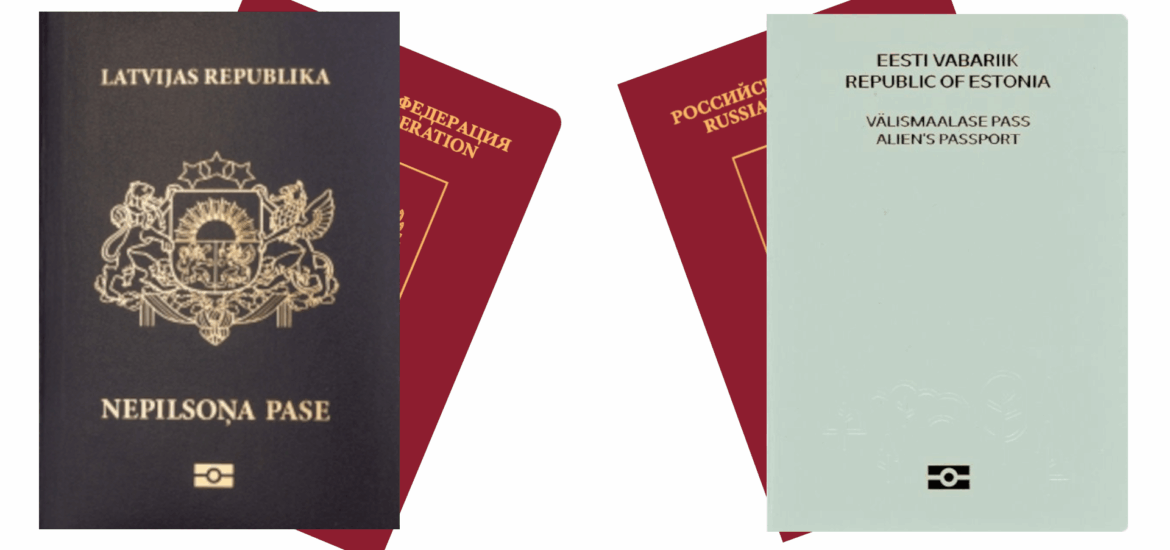

As a result hundreds of thousands of Russians and other orphans of the Soviet Union were issued with brown or grey alien passport. Those were confirming their identity and right to reside in, respectively, Latvia or Estonia, but stopped short from granting them citizenship. Of course those who were willing to integrate could easily become citizens, but, as part of the integration program, they were expected to pass exams from the official language of the country.

For most of the people this was the obvious path to take (especially after 2004, as this gave them easy access to EU citizenship). But some weren’t interested. They did not believed they need to learn the local language, they could easily get by using only Russian – especially that, while this is changing with the new generations, the older generations still commonly speak fluent Russian. And, last but not least, why go to so much trouble, if Russia will easily give them Russian passports, no question asked (which is part of their imperial politics – for the very same reason Hungarians give Hungarian passports left and right to pretty much anyone living in the areas that Hungary lost after the Trianon treaty).

In result, while Estonia and Latvia were moving ahead, this group – with numbers dwindling with time, but still significant – lived in a kind of Russian-language bubble, not showing any interest in being naturalised or integrated. And more the Baltic States were moving to the West, more deeply they were crawling into this Russian world, that gave them a sense of security nad belonging. They were taking all their news from Russian media and TV – which was clearly visible during the recent Russian president vote (i am deliberately not using word “election here”, as there is no election if you have no choice) when Western journalists were interviewing Russian queuing to vote in the embassy in Tallin only to be shocked how widespread love for Putin is amongst the people who, in many cases, haven’t visited Russia for decades. Up to some point, Baltic States tolerated this, as the demographic data of this group clearly showed, that the problem will disappear with time by itself, so to speak.

The circumstances changed after Russian full scale war on Ukraine. Not only aforementioned bullshit about the need to defend Russian speakers suddenly became a valid concern, but it has become clear, that Russian who live in Europe but are still loyal to Putin are a huge recruitment pool for Russian agents brought the government’s attention to the issue. The governments of Latvia and Estonia concluded, that they can’t just tolerate the situation any more, and gave their residents ultimatum: either you finally do something to show you’re willing to integrate and pass a simple language test, or maybe you should think about living in the country that you clearly feel more connections to.

One of persons who fell victim to those changes is Galina Nikolaieva, as shown in the Deutsche Welle reportage above. She’s 74 years old, and despite living in Latvia since she was 10 (half of this time in an independent Latvian Republic!), and despite declared love to the country she spent all her life in, she never bothered to learn enough Latvian to pass a test at B1 level (for comparison: I live in Finland for 3 years now, and I passed my B1 6 months ago). As the government asked her to leave, she is now de-facto an illegal alien.

Vast majority of comments I’ve read on the internet enthusiastically supports new politics of Baltic States towards their Russian residents. I noticed many voices coming from the young generation, that seems to be really happy that those Russians, who can’t come to terms with their lost privileges, and often come as far as to vulgarly abuse young people who can’t (or won’t – to which they have right, as it’s their country) speak Russian with them. What came as a surprise to me was that those few voices in defence of Galina, do not come from the position of sympathy, but from the imperial point of view. “It’s like if we required all migrants in Dublin to speak Irish, or Navaho if they want to move to America” wrote one person, clearly unaware that the very reason that first nation languages, or the Irish Gaelic are not dominant languages there are the results of the fact, that not only the newcomers were not required to learn the language in order to settle there, but its use was actively persecuted. So if those examples were to bring anything to this discussion, they should be used as a cautionary tale in support of the current government’s decisions that aim to defend their language from Russian linguistic imperialism.

And do I feel pity for Galina? Not really. I am simply fascinated by her mindset, as I see it as a prime example of the way of thinking of a Russian orphaned by the Soviet Union.

“If I was 65, I would try to pass those exams, but I am too old now” – argues Galina. It might be so, but when Latvia re-gained its independence, Galina was 40 years old. If she thinks she would be able to learn basic Latvian 10 years ago, surely it would be even easier for her a few decades further in the past? Yes, one can argue that back then it was not required. It is true, but still, it was required from those who wanted to integrate and gain Latvian citizenship. For many Russians it was not worth the hassle, especially that it was much easier to get Russian passport. Galina is clearly a member of this group, as in one of the scenes she is shown using her red, Russian passport, and not the brown Alien passport that was issued to people like her by the Latvian government.

Stil, even if getting the Russian passport was easier, it still surely required some effort. She probably had to visit an embassy, fill some paperwork, pay some fees. One can think that if she went through all this trouble, she feels a connection to this country – in a way proportionally stronger to the country that she spent all her adult life in. That was her choice. And so, she is still not required to pass her Latvian test. She is free to observe decision of the Latvian government and move to the country, that she went through all this trouble to obtain citizenship of.

Galina claims to love Latvia, but it’s clear that she never got any interest in its culture (she would surely get to B1 just by osmosis if she tried to watch Latvian TV, had some Latvian-speaking friends or at least try to exchange few sentences with the cashier when taking groceries over all those years). We also have to remember, the new rules are result of a decision of a democratically elected government. Elected by the country’s citizens. Galina was clearly not interested to participate in the political life, as if she was, she’d try to become a citizen. This is very typical for all those conversations with Russians that I watch – they all say “I am not into politics” (although, we have to remember that under current climate it’s an understandable excuse to avoid talking on the subject where saying one word too much might result in long prison sentences). But this approach has one issue: you might not be interested in politics, but sooner or later politics will be interested in you.

I will permit myself to speculate a little: of course we don’t know that, but it is very likely that she was taking part in elections, but those were elections in Russia. And if she did, then I think it’s a safe bet she voted for Putin.

Another thing is that while it is indeed not required to learn the local language in order to live in some country, as someone who emigrated from Poland 20 years ago, I can’t imagine spending such a big part of my life limited only to a Polish-speaking ghetto, even if it’s as big as the Polish community in the UK. And learning the language is just the beginning – even if you speak English at C2, you will never be able to fully embrace Glasgow culture without knowing all those cult quotes from TV shows like Chewing the Fat for example.

Of course Galina’s and mine situations are quite different. While populating occupied territory with Russians was deliberate action of the Soviet government, in order to dilute local language and culture (and potentially, as we can see on examples of Moldova, Georgia or Ukraine, to lay territorial claim based on presence of Russian speaking population), for ordinary Russian this was not necessary the reason for their move. They weren’t willingly leaving their own country behind, it was the border that moved, leaving them outside. But just like many migrants, they might not feel the same connection as natives to their country of residence, while at the same time feeling as an outsider in their country of origin. I first became aware of this during my classes at Glasgow University, when I noticed that my professor Jan Čulík, a Czech living in Scotland since 1978 uses a phrase “They here” when talking about Scots or Britons, and “Them there” when he talks about Czech”. The only instances when he used the word “we” is when he was talking about our group at this current moment, or when he referred to his closest family. But somehow with those orphaned by the Soviet Union it happens that those, who don’t want to integrate usually feel quite strong connection to Russia.

In summary: for over 30 years Galina lived in the independent Latvia, yet despite her claims she loves the country and considers it home she never made any effort to integrate. On the other hand she bothered to obtain passport of the Russian Federation, the country she never in her life lived in (she came to Latvia at the age of ten, after spending her early childhood in Uzbekistan). This is the time, when she has to face consequences of ther life choices. The only reason why she can feel as a victim is probably that she thinks, that as a Russian she has right to live in Latvia as long as she pleases. And I think this is the core of this issue: this is a part of a wider phenomenon, once described neatly by Václav Havel, who said that the problem with Russia is that it is unable to understand where it begins and where it ends. On the macro scale it means that the country leaderships considers every place where a Russian tank (or, recently, more likely a battered Moskvich with a drone cage welded from pieces of stolen Ukrainian fence) can reach is considered a Russian land. On a micro scale it means that Russians like Galina are unable to comprehend, that being Russian does not give anyone any privileges outside Russia, at least not anymore. In another recent Deutsche Welle reportage, about Estonian decision to no longer allow Russian citizens to vote in Estonian election, I noticed an utterance from one of such Russian, who seemed to be outraged by it: “it’s as if [Russians] were second class citizens!” she says.

Dear lady, if the Baltic States treated you for more than 30 years as “second class citizens”, you should be very grateful to them for being so nice to you. Because unless you pass your language test and apply for Estonian passport, you are not a citizen at all. Not a second class citizen, not a seventh-class citizen and not a twentieth-class citizen. Is this really so hard to comprehend?

passport pictures: public domain