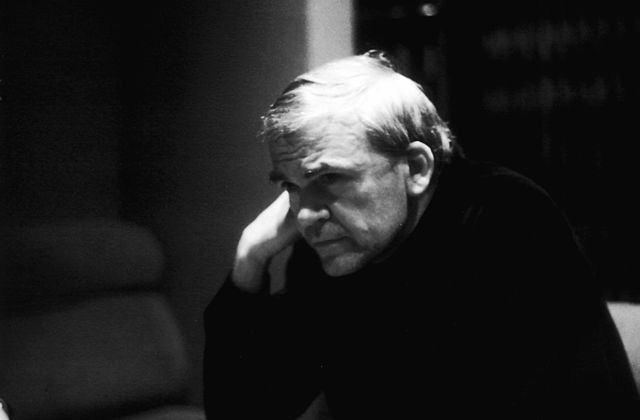

Milan Kundera is a writer who sits astride between the West and Eastern Europe. Being born in Brno he spent his first half of life in Czechoslovakia. Since 1975 he has been living in France. His work life can be divided into two parts, demarcating two different periods – before and after immigration. This unique position he finds himself in allows him to explain Eastern Europe to the Westerners. In his 1983 essay „A kidnapped West” he points out that thanks to the events which followed the Second World War, Eastern Europe culturally belongs to the West and geographically to the Central Europe, but politically to the East 1. This observations play a vital part in his book „Slowness”. Kundera not only explains Eastern Europe to the people of the West but also he has no hesitation to criticise the West.

Experiences of a “Slowness” character, a Czech scientist who suffered under the communism, shows a total lack of Western interest in Eastern Europe. When his country rejoins European family, he returns to the scientific community but he finds that there is no common ground for communication. His Western colleagues talk about how things are in their own countries but when he tries to tell them how the things are done in his country, they momentarily loose their interest2. People from the West do not pay much attention to a proper spelling of his name3. Later, a politician proves a complete ignorance to Eastern Europe – for him Prague, Budapest or nationality of Mickiewicz makes absolutely no difference4. As shown by Martin Pollack in his recent essay „Where East meets West”5, even after fifteen years since Kundera wrote “Slowness” it has been very typical for the Westerners to show little interest in culture and affairs of Eastern Europe.

Experiences of a “Slowness” character, a Czech scientist who suffered under the communism, shows a total lack of Western interest in Eastern Europe. When his country rejoins European family, he returns to the scientific community but he finds that there is no common ground for communication. His Western colleagues talk about how things are in their own countries but when he tries to tell them how the things are done in his country, they momentarily loose their interest2. People from the West do not pay much attention to a proper spelling of his name3. Later, a politician proves a complete ignorance to Eastern Europe – for him Prague, Budapest or nationality of Mickiewicz makes absolutely no difference4. As shown by Martin Pollack in his recent essay „Where East meets West”5, even after fifteen years since Kundera wrote “Slowness” it has been very typical for the Westerners to show little interest in culture and affairs of Eastern Europe.

Kundera gives a good explanation to this ignorance. In „Kidnapped West” Kundera points out many differences between Western Europe, Europe of the big, strong countries and Eastern Europe, where small nations had to struggle for survival between the big powers of the East and the West. Kundera defines a small nation as „the nation which existence can be questioned at any time, which can disappear at any time and is aware of this. French, Russians or English do not ask themselves a question if their nation will survive. Their national anthems speak about greatness and importance. Polish national anthem in turn starts with words „Poland has not yet perished…”6 This is the reason why the French colleagues of the Czech scientist in „Slowness” are moved by his story, but being Westerners they are unable to understand him.

Despite this ignorance, people from the West still have a strong feeling of some cultural superiority. Berck, a politician or maybe just a celebrity, who just happened to be at the conference tries to use the Czech scientist to boost his popularity by showing off with his altruism in front of the television cameras. In fact, however, while he talks about respect he has to the Czech scientist and Eastern Europeans as a whole, he shows a great disrespect. And despite his complete ignorance about the subject he treats the poor entomologist in a patronising manner7. The same evening a cameraman, rejected by Immaculata, a journalist he works for and had an affair for some time with, turns against the Czech. Immaculata jumps into the water and the entomologist, who witnesses it, rushes to help her while the cameraman stands still. It is only when he saw the Czech’s actions, he starts to act, but instead of helping her, he stands behind him. „He knows nothing about this man, he has no reason to mistrust him but, blinded by his suffering, he sees in this monument of ugliness the image of his own inexplicable misery and is gripped by an invincible hatred for the man”8 One can easily derive parallel to the real events from the Western history – for example respectively to the use of Eastern Europe during the World War II and then completely ignoring its voice or in current situation in Britain where working class people turns again Polish workers who came and took the jobs they weren’t willing to undertake in a first place.

The picture of the people from the West painted from the point of view of the Czech entomologist does not encourage the reader to respect them too much. The Czech had great hopes regarding his visit to the conference in a French castle, but all he experienced was a discreditation when he was so moved that he forgot to present his discoveries, humiliation by Berck and finally losing of his teeth in a fight with the cameraman. On the contrary even the work on the construction sites, a part of his life he hoped to forget, gave him „a palpable souvenir: an excellent physique”, the one that none of the people present in the castle possibly had9.

The relation to the Eastern Europe is not the only thing in the West criticised by Kundera. For example media manipulation: when Kundera and Véra arrive to a château, they watch TV where scenes from famine in Somalia are shown. But one can see only hungry kids – there are no hungry adults or elderly people. The media manipulation allows to create an action when French kids collect and sent rice to Africa and the whole process becomes more important than famine itself10. Then the pictures from Africa give place to the commercial in which sex is used to sell the best way to wash nappies11.

Sex in a „western way” is also put to shame by Kundera – the fling between Vincent and Julie, who makes a row about it, running around the corridors, shouting, swimming naked and finally having sex at the edge of the hotel swimming pool. But despite Vincent’s blusters („I’ll stick my cock through you and nail you to the wall”12) his member is too small to succeed. Yet both Julia and Vincent pretend that everything is all right and simulate the copulation.

Another interesting concept is a comparison of politicians to dancers – both have to take over the stage. But this requires keeping other people off it. To achieve it politician-dancer has to use a tactic called a „moral judo”: „who can appear more moral (more courageous, more decent, more sincere, more self sacrificing, more truthful) than he? And he utilizes every hold that lets him put the other person in a morally inferior situation”13 As Kundera himself says „Anyone who dislikes dancers and wants to denigrate them is always going to come up against an insuperable obstacle: their decency”14 There is no way to oppose it – as in a situation when the politician asks publicly „‘Are you prepared right now (as I am) to give up your April salary for the sake of the children of Somalia?’ Taken by surprise people have only two choices – either refuse and discredit themselves as enemies of children, or else say ‘yes’ with terrific uneasiness, which the camera is sure to display maliciously15” Everyone can see through that mystification, but if one wants to stay in a game, there is no other option as to play along with these rules. This bears the analogy to the situation from two centuries earlier: the lady who plays games with the Chevalier and turns a kiss into an act of resistance – he is not fooled but „he must none the less threat these remarks very seriously because they are part of a mental procedure that requires another mental procedure in response”16 This conception, presented from the antiquity assumes cycles of time (not linear

chronology) and everlasting repeating of constant, unchanging formulas17, comes along with the ideas Kundera examined in „The unbearable lightness of being” – Nietsche’s idea of everlasting circle.

There is one significant factor with which contemporary Western world can be associated: the speed of life. It has a huge influence on the way people live nowadays. „Speed is the form of ecstasy the technical revolution has bestowed on man (…) A curious alliance: the cold impersonality of technology with the flames of ecstasy”18 It is speed which screens people from their life – like a motor biker who, unlike a runner, does not feel the speed with his body but, thanks to the physical aspects of the movement taken over by the machine, can experience ecstasy of non-material, pure speed19. „The man hunched over his motorcycle can focus only on the present instant of his flight, he is caught in a fragment of time cut off from both the past and the future”20 In that state he is unaware of anything and as a person he is freed from the future and he has no fear. This everlasting pursuit for ecstasy of speed stripped today’s man of the pleasure of slowness. There is no longer a place to stop and enjoy a beauty of the nature, art or just pleasure of pure laziness. „In our word indolence has turned into having nothing to do (…) a person with nothing to do is frustrated, bored, is constantly searching for the activity he lacks”21 In today’s world thanks to the technological advantages we listen to the music on the run, we read on the bus and, as observed by Kundera in his „Kidnapped West” essay, we no longer enjoy painting. But since religion is no longer something to unify Europeans, we had only the arts and ideas and the art is also giving up that field22. There seems to be no place for ideas in this fast and crazy world. As it was observed by the Czech entomologist „When things happen too fast, nobody can be certain about anything at all, not even about himself”23

This is the reason why Chantal, a main character of next Kundera’s book „Identity”, becomes unsure of who she is. In her pursuit of happiness she has to put on different masks all the time. In her marriage she had to play along with the rules and pretended that she liked her life in the family of her husband. Her situation may be compared to the dancers in „Slowness”. Chantal could not openly say that she was unhappy, without instantly falling out of the game. After her child’s death, Chantal left her husband and started a new chapter of her life with a lover Jean-Marc. Nevertheless, she was still putting different masks and in the end of the book we can see she was no longer able to tell her name. The reader cannot tell if her new life with Jean-Marc is real or if it was a dream or an imagination, unleashed by the death of her baby. Just like Vincent in „Slowness” who knows, that only an invented story can make her forget what happened in reality.24

„Identity” deals with more universal, psychological issues. It is „Slowness” that really deals with Western culture and as spotted by Krzysztof Rutkowski, Kundera tries to pass a message to French sex maniacs „You are talking too much, this is why you get it wrong” and to the Parisian intellectuals „I understand your game, I could play it as well if I wanted, but I don’t”25.

Milan Kundera is one of a few Eastern European writers recognised in the West – to such an extent that he is considered to be a French writer. Kundera when writing „Slowness” has lived in the West for nearly 20 years. This essay examined his perception of various aspects of the Western culture. In my opinion he proves that he understands it well, yet he refuses to take a part in many aspects of the Western life. This shows clearly how much he disdains it.

1 Milan Kundera „Zachód porwany albo tragedia Europy Środkowej” “Zeszyty Literackie”, nr 5, Paris 1984

2Milan Kundera „Slowness” translated by Linda Asher, Faber and Faber, London 1996 p. 46

3ibid, p. 47

4ibid, p. 67

5Martin Pollack „Where East meets West” in „New Eastern Europe” 1/2011, Kraków-Wrocław 2011

6 Milan Kundera „Zachód porwany albo tragedia Europy Środkowej” “Zeszyty Literackie”, nr 5, Paris 1984, (my own translation)

7Milan Kundera „Slowness” translated by Linda Asher, Faber and Faber, London 1996 p. 67 and next

8ibid, p. 111

9ibid, p. 80

10ibid, p. 13

11ibid, pp. 13-14

12ibid, p. 101

13ibid, p. 18

14ibid, p. 20

15ibid, p. 18

16ibid, p 28

17 Alicja Głuszyńska , licentiate thesis „Milan Kundera – więzień świata między Wschodem a Zachodem”, SWPS, Warszawa 2009 (my own translation)

18Milan Kundera Slowness” translated by Linda Asher, Faber and Faber, London 1996 p. 4

19loc. cit.

20ibid, p. 3

21ibid, p. 5

22 Milan Kundera „Zachód porwany albo tragedia Europy Środkowej” “Zeszyty Literackie”, nr 5, Paris 1984

23Milan Kundera Slowness” translated by Linda Asher, Faber and Faber, London 1996 p. 114

24ibid, p. 126

25 „Garkuchnia Kundery”, Krzysztof Rutkowski „Gazeta Wyborcza” 113/1995

Picture: „Milan Kundera“ by Elisa Cabot – Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.