For centuries, Russian settlement expanded the Russian empire. Settlers assimilated nations on the frontiers of the Empire. Huge areas of unpopulated land in Central Asia provided space for everyone to live beside each other, but the influence of Russian modern culture on their neighbours was overwhelmingly strong. Colonisation of Western borderlands was much more difficult and forced russification of the occupied territories resulted in a hostile attitude towards Russia.

At the beginning of the Soviet Union the Bolsheviks had called for the national self-determination of all peoples and had condemned all forms of colonisation as exploitative. After gaining power, however, they had a strong desire to hold on to the all of the lands of the former Russian Empire.1 To justify this, they tried to portray the new Soviet Union as a “Empire of Nations” and the country was constructed as a federation of formally independent national republics. But Stalin already in 1913 year in his essay “The Nationality Question and Social Democracy” „attacked the principle of extraterritorial autonomy on the grounds that it strengthened national differences, which would otherwise dissipate as class consciousness grew” He argued that proletariat, not nation, is important and as each nation has its own distinctive class system, then this makes cooperation between them more difficult compared to international communication between worker’s2. Soon it became clear that the smaller’ republic’s right to self-determination is limited when the Russian interest is considered. In Kazakhstan, for instance, there were a significant amount of Russian settlers who came during the tsarist period. Kazakh communists seized their land, considering this as nation-building and reparation for colonial injustice. The „Kazakhstan to the Kazakh” politics was continued and in 1925 the Fifth Kazakh Party conference practically outlawed for 10 years immigration from the other parts of USSR. In January 1928, the Moscow CC forced Kazakhstan SSR into the general Party line by a series of purges3.

At the beginning of the Soviet Union the Bolsheviks had called for the national self-determination of all peoples and had condemned all forms of colonisation as exploitative. After gaining power, however, they had a strong desire to hold on to the all of the lands of the former Russian Empire.1 To justify this, they tried to portray the new Soviet Union as a “Empire of Nations” and the country was constructed as a federation of formally independent national republics. But Stalin already in 1913 year in his essay “The Nationality Question and Social Democracy” „attacked the principle of extraterritorial autonomy on the grounds that it strengthened national differences, which would otherwise dissipate as class consciousness grew” He argued that proletariat, not nation, is important and as each nation has its own distinctive class system, then this makes cooperation between them more difficult compared to international communication between worker’s2. Soon it became clear that the smaller’ republic’s right to self-determination is limited when the Russian interest is considered. In Kazakhstan, for instance, there were a significant amount of Russian settlers who came during the tsarist period. Kazakh communists seized their land, considering this as nation-building and reparation for colonial injustice. The „Kazakhstan to the Kazakh” politics was continued and in 1925 the Fifth Kazakh Party conference practically outlawed for 10 years immigration from the other parts of USSR. In January 1928, the Moscow CC forced Kazakhstan SSR into the general Party line by a series of purges3.

During the 1930s Stalin realised, that nation building brings unexpected consequences. Nations trying to gain autonomy and „the resistance the nations had offered to the ‘revolution from above’” convinced Stalin that russification is a more reliable mean to establish the central dictatorship4. He started a politics of forced migration and encouraged Russian people to settle in other republics. „Stalin perceived the new sovietized Russian intelligentsia as a reliable instrument of controlling the empire, particularly the non-Russian territories”5. During period of de-Stalinisation there were some attempts to re-establish a higher level of natives within top positions in local Parties, soviets and economies, for example, all three Baltic republics replaced their Russian second secretaries with natives, but it did not last long6 as the Russian’s positions in the other republic’s authorities were already well established. In the summer 1954 a policy of forced settlement of all deported peoples was relaxed, which caused huge migrations of many nations and further weakening of national unity within some republics.

As a result of such Policies in 1960s the population of all Soviet republics was fairly mixed with a significant leading role given to Russians. Due to the amount of Russian settlers all around the USSR, “Russian language and culture has had special status throughout the Soviet Union. The Russian language has been the common language in government organizations and cultural institutions. Higher education in many fields has been provided almost exclusively in Russian”7. Native communist elites were purged and replaced with Russians or thoroughly russified persons8. Russian settlers were often seen as ambassadors of Soviet culture and way of life. This applied especially to the Red Army soldiers allocated to all republics. „The Soviet armed forces were meant to promote ‘The School of the [Soviet] Nation’. Soldiers were mostly Russian or russified. Although each military unit was ethnically mixed, over 95% of top Soviet officers in the Red Army were Russians.9” Along with the influx of a Russian-speaking population accompanied by Russian cultural expansion, the smaller republics experienced also a “brain drain” as local intelligentsia, who were often struggling to compete with newcomers taking advantage of special treatment, sought their chance in Moscow or other republics. That lead to many protests, for example in 1964 „the Initiative Committee of the Ukraine’s Communists protested against both the emigration of Ukrainian intellectuals to the centre (the Russian SFSR) and the mass migration of Russians and Russian speakers to the Ukraine10”.

Integration of local nations with the rest of the Soviet society wasn’t related to merely the number of Russian settlers. The length of the period of Russian settlers cohabitation with local nations was also a significant factor. For instance, „the Islamic peoples in the Volga region, who were already integrated into Russia during the sixteenth century took over local Soviet power far more successfully than the Islamic peoples in the Northern Caucasus, which the Russians had only conquered in the nineteenth century11”.

Despite demographic changes in 1960s and 1970 when the Russian majority in the whole Soviet Union was whittled down, still, a majority of the titular nationalities in each of the republics decreased considerably. In 1979 the Kazakh and Kirghiz even became minorities in their own republics12. Thanks to their wasteful exploitation of the smaller republics, Russians were often seen as conquerors. Also heavy russification caused growth of national consciousness. As Belorussian dissident Mikhail Kukobaka described: „[After I left labour camp where I spent several years] I sighted an inscription on a turnpike. Twenty-five years ago it was written in Byelorussian with the Russian translation below. Now the Byelorussian phrase has disappeared. To my surprise, this offended me. Suddenly I realised that I am a Byelorussian.”13. As a result of seeking an alternative to Russian domination, “between the 1960s and 1980s all ethnic minority movements (…) demonstrated strong pro-Western orientations”14.

A case study of Estonia allows a closer look to the Russian settlement problem. Estonia has always had an indigenous Russian population, but in the 1920s there were also a number of refugees from Bolshevik Russia. A majority of them did not have Estonian citizenship. In 1945–1980 mass colonisation by the Soviet Union increased the Russian population in Estonia drastically. The colonists commonly viewed the local Russians as anticommunist. Afraid, and sometimes even ashamed of their Russian origin, Estonian Russians started to call themselves Estonians15. The centralised economy of the Soviet Union wasn’t considering either the local resources of raw materials, or local needs, heavy industry boomed ant outgrew Estonian capabilities. Due to lack of workers Estonia experienced a huge influx of workers from other parts of the USSR. “Between the years 1945 and 1950 the population of the Estonian SSR, which was of about 850 000 of mostly Estonian people, increased by a further 170 000, who formed compact Russian speaking settlements in Estonia. In 1959 a Russian-speaking minority formed one-quarter of the population. (…) [That] caused a language problem, solved in favour of Russian. Soon many native Estonians were struggling to cope as they weren’t speaking it”16. During the Soviet period, also Russian villages in eastern Estonia underwent profound changes. Young people moved to towns and few retained any connections with their home villages17 which helped in their ‘sovietisation’. In the 1972 manifesto to the UN, Estonian national movements pointed that Estonia’s industrialisation „serves as a cover for russification” as “that industry, governed directly for Moscow, had no connections to economy and needs of Estonia”. Since Estonia has been forced into Soviet Union, it’s industrial output has increased by 2779%, when for the whole USSR that increase was only 1188%. This disproportionate growth demanded numerous workers, which gave a pretext to move in mostly Russian settlers18. Development of industry became even more extensive in late 1970s and as a result in 1980s Estonians formed less than 65% of the population. As a result of settlement policy favouring newcomers over locals some industrial areas in eastern Estonia became completely Russian speaking and the few remaining Estonians left the towns. Lack of hope and prospects for the future caused pessimism leading to depression (often suicidal) and alcoholism among the Estonian community19. Meanwhile Estonia’s contacts with the Western World resulted as Estonia being seen in the rest of USSR as a „Western oasis”, which encouraged further migration from the other parts of the Soviet Union20.

Tensions between people became a major issue when colonists, who were often seeing Estonians as former German collaborators, who “can’t even speak a human language21” and benefited from the civilisation brought to them by Soviet liberators, found themselves left alone after collapse of the USSR. „The colonists’ options were limited. (…) Most colonists were stuck in Estonia, wherever they wanted this or not. The question was how rapidly they would become sufficiently bilingual to function under post-colonial conditions”22.

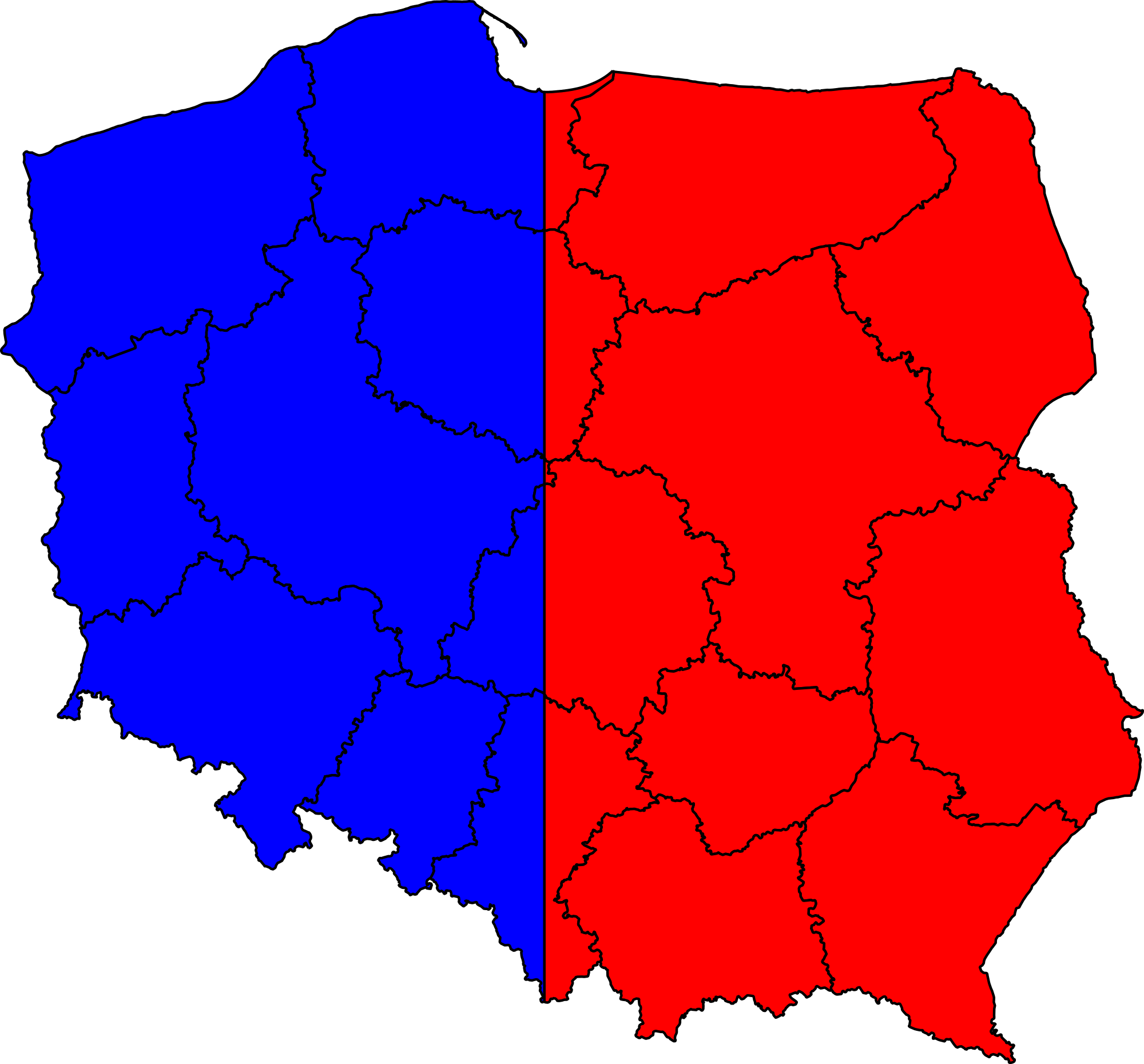

Completely unique case is the Kaliningrad District. Here, the Russian settlers almost completely replaced previous German population so it’ was not a case of the settler’s influencing the local community. But in the 1990s this area became an Russian enclave surrounded by pro-Western independent countries. Russian demands for a transport corridor linking Kaliningrad with nearby Belarus through Polish territory in 1996 has cast a shadow on Polish-Russian relations23. This and related problems give Russia pretext to put forward it’s own claims towards stricter European cooperation24 and give it a chance to influence internal EC politics as all surrounding states have to take account of the Russian military presence in the area.

70 years of the existence of the USSR had a major impact on the nations involved with it. Severe russification often resulted in a weakening of the nation’s cultural life and language. Vast numbers of Russian-speaking settlers pulling towards Russia is a major issue for small Western-orientated countries. But the necessity of standing up against Russian-Soviet influence helped to develop national self-consciousness amongst these small nations. Russians also suffered. Many Russians after spending often their whole lives in some places suddenly found themselves foreigners in their own homeland. From Moscow, separation of the former Soviet republics is seen as ingratitude towards Mother Russia, which delivered civilisation to them and admitted them into the Soviet family. This is the unification of “Soviet” and “Russian”, that made Russians feel as losers after the collapse of the USSR. There is a famous poster showing children of all Soviet nations marching on Red Square. All of them wear national clothes except a Russian boy, who wears a Pioneer’s organisation uniform. This poster reflects Soviet reality, where the Russian nation placed itself above others. For this right to identify with a Soviet Empire, Russians had to pay with the partial surrender of their own national identity, tradition and culture25.

1 Francine Hirsch „Empire of Nations: ethnographic knowledge and the making of Soviet Union” , Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London 2005 p. 5

2 Hirsch, op.cit. p. 27

3 Gerhard Simon „Nationalism and Policy Toward The Nationalities in the Soviet Union”, Westview Press, Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford 1991, p.81

4 Simon, op.cit. p. 138

5 Simon, op.cit. p. 265

6 Simon, op.cit. p. 229

7 http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+su0094) Accessed 24 III 2009, 00:10

Temporary sub-site of http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/sutoc.html#su0094 – A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former)

Library of Congress Call Number DK17 .S6396 1991

8 http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+su0128) Accessed 24 III 2009, 00:12

Temporary sub-site of http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/sutoc.html#su0094 – A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former)

Library of Congress Call Number DK17 .S6396 1991

9 Miron Rezun [Ed.] „Nationalism and the breakup of the Empire” Praeger, Westport Connecticut, London 1992. p. 6

10 Diana Zieserman-Brodsky „Constructing Ethnopolis in the Soviet Union”, Palgrave McMillan, New York 2003 p. 41

11Simon, op.cit. p. 38

12 http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+su0128) Accessed 24 III 2009, 00:12

Temporary sub-site of http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/sutoc.html#su0094 – A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former)

Library of Congress Call Number DK17 .S6396 1991

13 Diana Zieserman-Brodsky „Constructing Ethnopolis in the Soviet Union”, Palgrave McMillan, New York 2003 pp. 91-92

14Zieserman-Brodsky, op.cit. p. 41

15Estonian Institute web page: http://www.einst.ee/factsheets/russians/ Accessed 23 III 2009

16 Mati Laur, Tōnis Lukas, Ain Mӓesalu, Ago Pajur, Tōnu Tannberg „History of Estonia” AS BIT, Tallinn, 2002 pp. 289-290

17Ibid. p. 289

18 The Estonian Democratic Movement, The Estonian National Front: Memorandum to the Secretary General of the United States Organisation, Tallinn 1972

19 Laur, Lukas, Mӓesalu, Pajur, Tannberg, op.cit. p. 301

20 Laur, Lukas, Mӓesalu, Pajur, Tannberg, op.cit. p. 295

21 Rein Taagepera „Estonia: Return to independence” Westview Press, Boulder – San Francisco – Oxford 1993 p. 220

22Taagepera, op.cit. p. 221

23http://www.stosunkimiedzynarodowe.info/kraj,Polska,stosunki_dwustronne,Rosja [International Relations.info] Accessed 23 III 2009

24Prof. dr hab. Marcin Rościszewski „Funkcjonowanie polskich regionów granicznych po przystąpieniu Polski do unii europejskiej (Próba prognozy geopolitycznej)” [“Functioning of the Polish frontier regions after Poland joined the European Union (Attempt of geopolitical prognosis)”] Centrum Studiów Europejskich [Centre for European Studies] Polska Akademia Nauk [Polish Academy of Sciences] www.rcie.lodz.pl/info/dokumenty/02_polska/opracowania/funkcjonowanie_polskich_regionow_granicznych.doc Accessed 20 III 2009

25 http://www.instesw.ebox.lublin.pl/ed/aktualny/matjunin_rec1.html.po [Institute of Central and East Europe in Lublin] – Accessed 24/03/2009